Scientists pay tribute to climate change pioneer, 75 years on

Release Date 22 April 2013

Global warming may seem like a relatively newly-discovered phenomenon - but climate scientists are this month celebrating the 75th anniversary of the breakthrough that helped kick-start research into one of the world's biggest scientific questions.

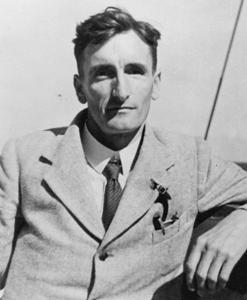

The global warming effect did not reach the mainstream of public consciousness until the 1980s. But the research that first confirmed the planet was warming was written by a British amateur climatologist, Guy Stewart Callendar, in April 1938.

Now scientists in the UK have marked the anniversary with a new research paper looking at the significance and legacy of Callendar's landmark findings.

Dr Ed Hawkins, of the National Centre for Atmospheric Science at the University of Reading, is the lead author of the new paper, alongside Professor Phil Jones of the University of East Anglia.

Dr Hawkins said: "In hindsight, Callendar's contribution was fundamental. He is still relatively unknown, but in terms of the history of climate science, his paper is a classic.

"He was the first scientist to discover that the planet had warmed by collating temperature measurements from around the globe, and suggested that this warming was partly related to man-made carbon dioxide emissions."

Despite making his groundbreaking discovery, Callendar did not receive widespread acclaim when he first published his work, Dr Hawkins said.

"People were sceptical about some of Callendar's results, partly because the build-up of CO2 in the atmosphere was not very well known and because his estimates for the warming caused by CO2 were quite simplistic by modern standards," Dr Hawkins said.

"It was only in the 1950s, when improved instruments showed more precisely how water and CO2 absorbed infra-red radiation, that we reached a better understanding of the importance of carbon emissions.

"Scientists at the time also couldn't really believe that humans could impact such a large system as the climate - a problem that climate science still encounters from some people today, despite the compelling evidence to the contrary."

Professor Jones added: "Callendar's estimates for the amount of observed warming have stood the test of time and agree remarkably well with more modern analyses of the same period."

What makes Callendar's work the more remarkable was that he was an enthusiastic amateur who made all the tedious calculations himself in his spare time, by hand, without the use of computers. By day, he was a professional steam engineer.

He also thought global warming was a good thing, because it would prevent the return of what he called the ‘deadly glaciers' and increase crop production at high latitude. But his work was key to restarting the debate over whether man could influence the global climate, Dr Hawkins believes.

‘On increasing global temperatures: 75 years after Callendar' will be published in the Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society - the same journal in which Callendar's paper was first published three-quarters of a century ago.

ENDS

For more details contact Pete Castle at the University of Reading press office on +44 (0)118 378 7391 or p.castle@reading.ac.uk.

Notes to editors:

Reference: Ed Hawkins and Phil. D. Jones (2013) On increasing global temperatures: 75 years after Callendar, Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. (in press)

Full paper available at: http://www.met.reading.ac.uk/~ed/home/hawkins_jones_2013_Callendar.pdf

The University of Reading is a top 1% global university (THE World University Rankings). Its Department of Meteorology and Walker Centre for Climate System Research make Reading one of the world's foremost centres for the study of global weather and climate.