Foodlaw-Reading

Dr David Jukes, The University of Reading, UK

Providng access to food law since May 1996

![]()

Foodlaw-ReadingDr David Jukes, The University of Reading, UKProvidng access to food law since May 1996 |

|

|

Last updated: 2 April, 2024

| On this page: |

On the 31st January 2020 at 11.00pm, the United Kingdom (UK) ceased to be a Member State of the European Union (EU) - 'Brexit' had been achieved. However the process of leaving the EU was difficult and many issues had still to be resolved. The UK and the EU had signed a Withdrawal Agreement which provided a legal framework for the process. A key part of this was for there to be a 'Transition Period' or 'Implementation Period' (IP) ending on the 31st December 2020. Until that point, the UK had agreed to operate under EU law. Although the Agreement allowed for the option of extending the Transition, the UK Government was against this and allowed the date for requesting an extension (30th June 2020) to pass without any request. Following extensive negotiations, a new relationship was finally agreed on 24 December 2020 in the form of a 'Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA)' to be effective at the end of transition - just 8 days later. The Agreement initially entered into force on a provisional basis but subsequently gained full approval by the EU. Certain other trade agreements with other countries were also agreed ready for the start of 2021 and additional ones have been adopted since.

Within the context of food law, there were many things which had to be decided either in the context of the overall agreement (e.g. any continuing access to the internal market for trade in goods) or with the details of food law requirements. The following are a few examples of issues which needed consideration - note that despite the adoption of a TCA, many issues linked to food law will only be developed with experience::

It has been necessary for the government to consider the future trading relationship with other countries, especially the USA, Canada and China. In some controversial areas (such as GM food and some food hygiene issues such as the use of chlorine to wash chicken), the demands of the EU seem to be incompatible with the demands of other countries - a political decision will then be required about which is more important for the UK's future.

In September 2022, the UK Government (with Prime Minister Liz Truss) announced its intention to end the use of 'retained' legislation with effect from 31 December 2023. The intention was that any controls considered still necessary would be incorporated into national legislation. To give effect to this decision, in September 2022 the Government introduced a Bill to Parliament, the Retained EU Law (Revocation and Reform) Bill. Following the change in Prime Minister in October 2022 (to Rishi Sunak), the policy was looked at afresh and, although some aspects of the Bill were passed, there were significant amendments meaning that substantial parts of retained EU legislation will continue to apply (and this applies to most food legislation). The new act, the Retained EU Law (Revocation and Reform) Act 2023, was adopted on 29 June 2023 and entered into effect from 1st January 2024. From that date, the terminology has changed: 'retained law' is now known as 'assimilated law'. It has been recommended by the FSA that 'this should now be identified or described as ‘assimilated law’, for example ‘assimilated Regulation (EC) 178/2002’ or ‘Regulation (EC) 178/2002 (assimilated)’'.

Devolution and the Ireland/Northern Ireland Protocol

Devolution:

The Ireland / Northern Ireland ProtocolThe United Kingdom is made up of 4 different components (England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland). Although many aspects of life are dealt with by the UK government in London, the process of devolution had provided the separate components with powers and authority to deal with certain aspects of their lives. With regard to food, the most important devolved element is health matters. As there has been this separation of power, legislation is often now adopted separately. As a Member State, this was not an issue as all 4 sets of legislation would be based on the common EU controls. Separate from the EU, this no longer applies and it is possible that within the UK some differences in the legal requirements will emerge. In an attempt to avoid this, the UK adopted the 'UK Internal Market Act' in December 2020. To assist in the effective operation of the Internal Market and to establish rules for matters with the potential for different legislation in the 4 components parts of the UK, the Act provides for the adoption of 'Common Frameworks'. Currently the following linked to food have been agreed on a provisional basis:

One of the most complex aspects of the Brexit process was determining the future relationship between Northern Ireland (a part of the UK and hence no longer a Member State) and the Republic of Ireland (still a Member State). There has been a treaty between the UK and the Republic of Ireland (the 'Good Friday Agreement' signed in 1998) which has provided for free movement of people and goods across the border between 'North' and 'South' along with other all-Ireland activities. This was relatively easy to implement when both North and South were EU Member States - common EU legislation applied to both countries. But what would happen if the UK decides to deviate from the EU requirements?

The Withdrawal Agreement includes an 'Ireland / Northern Ireland Protocol' (frequently referred to simply as the 'Northern Ireland Protocol' at least in the UK) which sets out the agreed rules. Under the Protocol, the UK has agreed that the legislation applied in Northern Ireland will remain consistent with many key components of EU legislation. This would continue to be the case even if the rest of the UK (England, Wales and Scotland - known together known as Great Britain) decided to adopt different requirements. Depending upon the changes adopted in the UK, this may result in requirements for checks and 'border' controls on goods entering Northern Ireland from the rest of the UK. During the Transition Period, the legislation remained the same but the requirements and the nature of checks after the Transition Period were complex and created disruption to trade.

Recognising these difficulties, following the changes in Prime Minister in the UK (from Boris Johnson to Liz Truss to Rishi Sunak), further negotiations took place. These resulted in the adoption, on the 27 February 2023, of a 'Windsor Framework' which allowed for certain goods, produced for sale in the UK, to enter Northern Ireland with reduced/no checks so longer as they were for sale in Northern Ireland. Any such goods could not be exported to the Republic of Ireland since they comply with UK legislation and not EU legislation. The implementation of this Framework is on-going.

This page aims to provide a summary of the status of food law (and in particular the relationship between UK and EU law) in the UK during this process.

During Transition (31st January 2020 - 31st December 2020)

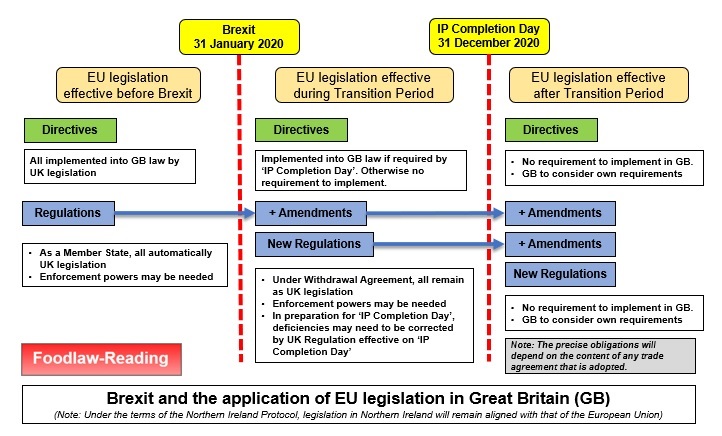

Under the terms of the Withdrawal Agreement, during the Transition Period (or 'Implementation Period' (IP)), nearly all EU legislation is still applicable in the UK. However, as the UK is no longer a Member State, there is no UK involvement in discussions about any changes to the legislation which may be effective during the Transition Period. After the Transition Period, Great Britain (GB) (i.e. the United Kingdom without Northern Ireland) is able to consider its own legal requirements (for Northern Ireland, see above discussion). This is summarised in the following figure:

A larger version of this figure is available as a pdf file - see: Brexit and the Application of EU Legislation in GB

Relevant News Items and Documents

After Transition (from 1st January 2021)

All EU legislation which was in effect at 11.00pm on the 31st December 2020, has remained as UK legislation after that time. Subject to the provisions of the Trade and Cooperation Agreement between the EU and UK, the UK government is able to adopt legislation which deviates from the EU requirements.

EU legislation is written on the assumption that it applies to Member States. The Regulations and Directives therefore incorporate procedures linked to the different EU components (for example, a Regulation might state: 'Member States will inform the Commission ...'). To ensure clarity and consistency in the legislation, using powers contained in the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018, during 2019 the UK Government adopted a lengthy series of Statutory Instruments to overcome any 'deficiencies' in the legal requirements. These were originally written to come into force on 'Brexit Day'. However this was changed and they entered into force on IP Completion Day. Many of these needed additional amendment to cover the final agreed deal - and, in particular, the Northern Ireland Protocol (see above).

Under the UK Internal Market Act 2020, there are provisions for the adoption of 'Common Frameworks' setting out the procedures for the exercise of collaboration between the 4 components parts of the United Kingdom'. The following relevant to food have been adopted:

For a listing of (1) UK Regulations which have been adopted to amend EU legislation to overcome deficiencies, and (2) EU legislation which has been subject to these amendments, see the separate page: UK Food Law - EU Legislation as Amended for the UK. The page provides direct links to the relevant document on the legislation.gov.uk website.

UK Legislation and Risk Analysis

As a Member State, the UK supported the risk analysis process developed and operated by the European Union. Scientific 'risk assessment' was mainly the role of the European Food Safety Authority, 'risk management' was shared by the EU's institutions (the Commission, the Council and the European Parliament) and the Member States. For 'risk communication', all elements had a role. With the UK being free to establish its own legislation, it will be necessary to provide a UK system of risk analysis to replace the EU one.

A guide to the planned system has been provided by the Food Standards Agency in the form of a report published by the Chief Scientific Adviser (published June 2020). See:

|

Risk Analysis: Chief Scientific Adviser's Report [Provided under the Open Government Licence. The original publication accessed from: |

With the departure from the European Union, the UK is responsible for all aspects of its legislation. This created a problem in that much of the legislation has only been published in the EU's Official Journal. On completion of the transitional period, it would have been inappropriate legally (and also politically) for the UK to be dependent on publications of the EU to provide the basis of UK law.

The European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 (in Schedule 5, Paragraph 1(1)) therefore included the following requirement:

The Queen’s Printer must make arrangements for the publication of —,

(a) each relevant instrument that has been published before exit day by an EU entity, and

(b) the relevant international agreements.

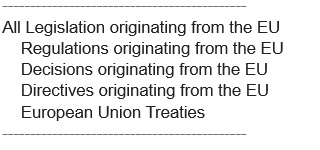

The European Union (Withdrawal Agreement) Act 2020 (in Schedule 5, Paragraph 48(2)) subsequently amended this provision to substitute 'IP completion day' for 'exit day'. The term 'relevant instrument is stated to include '(a) an EU regulation, (b) an EU decision, and (c) EU tertiary legislation;'.

It should therefore be possible to identify within UK publications, all relevant EU legislation that existed on IP completion day. This can be accessed from the main site: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/. From the main search tool at the top of the page, the drop-down list for 'Type' now includes the following towards the bottom:

The amount of legislation that needed to be included was large and the process of including it took some time. Note however that various UK Regulations may include provisions which amend the EU legislation, in particular to overcome 'deficiencies'. Care will be needed to ensure that the fully updated and amended version of any EU Regulation is consulted - the legislation.gov.uk site is attempting to provide this ability. Note that formatting on the UK legislation site may not be ideal and, in some cases, it might be preferable to also check the original version of the EU legislation to verify the precise legal requirements.

For an official description, see: EU legislation and UK law provided on the legislation.gov.uk site.